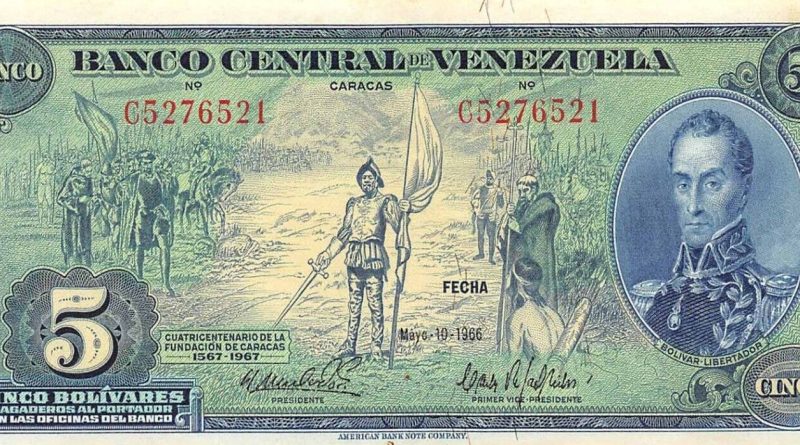

When history is sketched – The Venezuela 5 Bolívares Commemorative Banknote, Issued in 1966

Currency serves as more than just a medium of exchange; it also reflects a nation’s history, culture, and identity. The Venezuela 5 Bolívares commemorative banknote, issued in 1966, is a remarkable example of how money can encapsulate significant historical events and national pride. Released to honor the commemorates the 400th anniversary of the founding of Caracas (1567-1967), this banknote stands as a tribute to the country’s struggle for freedom and sovereignty.

The story of Venezuela’s colonial invasion begins with the first Spanish incursions in the early 16th century, driven by the pursuit of gold, pearls, and new trade routes. Arriving on the coasts of what is today eastern Venezuela, the conquistadors soon established small settlements that would serve as strategic footholds for further exploration. The indigenous communities, accustomed to their own thriving networks of commerce and governance, found themselves confronting Spanish aggression and the imposition of unfamiliar societal structures.

Resistance was fierce and persistent. Indigenous leaders orchestrated campaigns of defiance against the encroaching colonizers, who, for their part, brought European weapons, diseases, and a demand for labor that radically altered local demographics. As the Spaniards pushed inland, they formalized missionary activities and introduced a plantation economy dependent on enslaved labor, thereby cementing the patterns of exploitation that would define the colonial era.

By the mid-16th century, the Spanish Crown had formal administrative control over large swaths of the territory, but regional alliances between indigenous groups and runaway slaves continued to challenge colonial stability. This turbulent blend of conflict, cultural convergence, and adaptation set the stage for the development of Venezuela’s social, political, and urban landscape, paving the way for the future emergence of a distinctly Venezuelan identity.

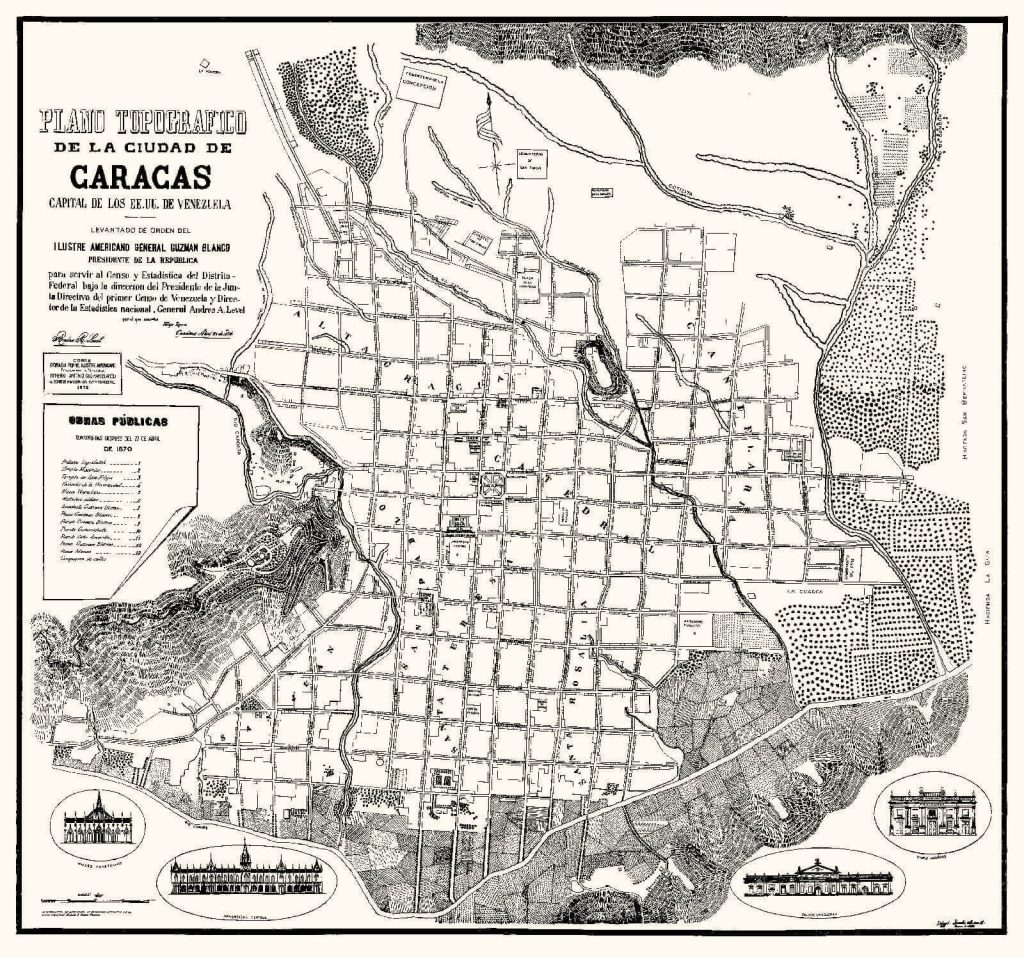

Situated in a valley nestled between majestic mountains and shielded from the Caribbean coast, the city of Caracas was founded in 1567 by Diego de Losada. The choice of location was anything but accidental. The natural defenses provided by the steep slopes of the surrounding mountain range, coupled with the relatively moderate climate, made the valley a prime spot for colonial settlement. Early Spanish settlers introduced agriculture, particularly cacao, which would become a cornerstone of local wealth in the following centuries.

Yet the foundation of Caracas was no mere act of fortuitous happenstance. On the contrary, it was a deliberate attempt to establish a seat of authority in a region that had already demonstrated a consistent spirit of resistance. Frequent conflicts with indigenous groups necessitated a strategic approach to urban planning. The early colonial administrators, guided by royal decrees, endeavored to create a city that could serve as a commercial hub and a bastion of political power.

During its nascent years, Caracas was organized around a grid system, adhering to the Laws of the Indies, which dictated the architectural and spatial composition of Spain’s New World cities. Plazas and churches occupied central positions, reinforcing the intertwined influence of colonial governance and the Catholic Church. These public squares were not merely ornamental; they were the literal and figurative centers of civic life. Markets, assemblies, and religious festivals were all staged in these open spaces, weaving a social tapestry that bound the city’s diverse populations together—Spanish, indigenous, African, and a growing number of mixed-heritage peoples.

Over time, as cacao exports grew and the Spanish Crown tightened administrative oversight, Caracas blossomed into a focal point of power. The relative geographic isolation encouraged a distinct culture to take root, blending European sensibilities with indigenous traditions and African influences. By the dawn of the 17th century, Caracas had firmly established itself as a critical stronghold of colonial Venezuela, presaging the influential role it would play in both the economic and intellectual life of the region.

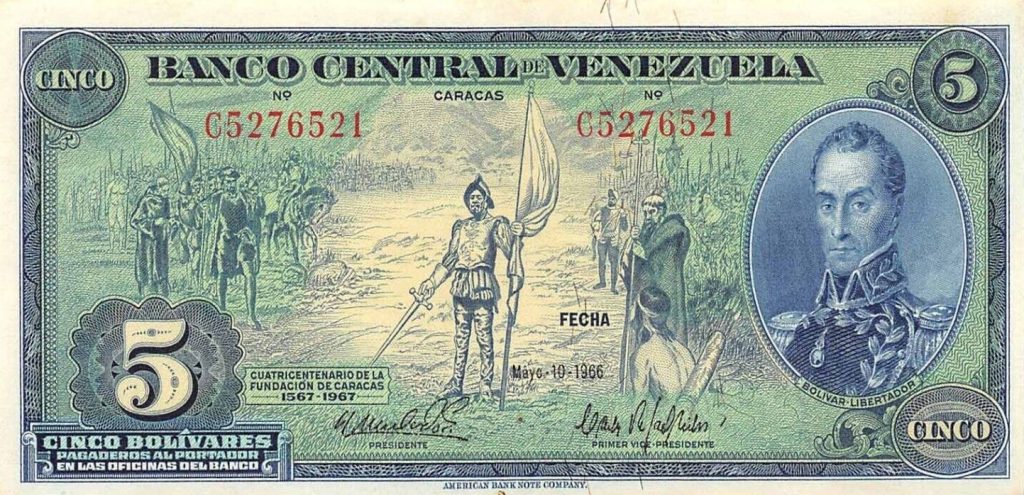

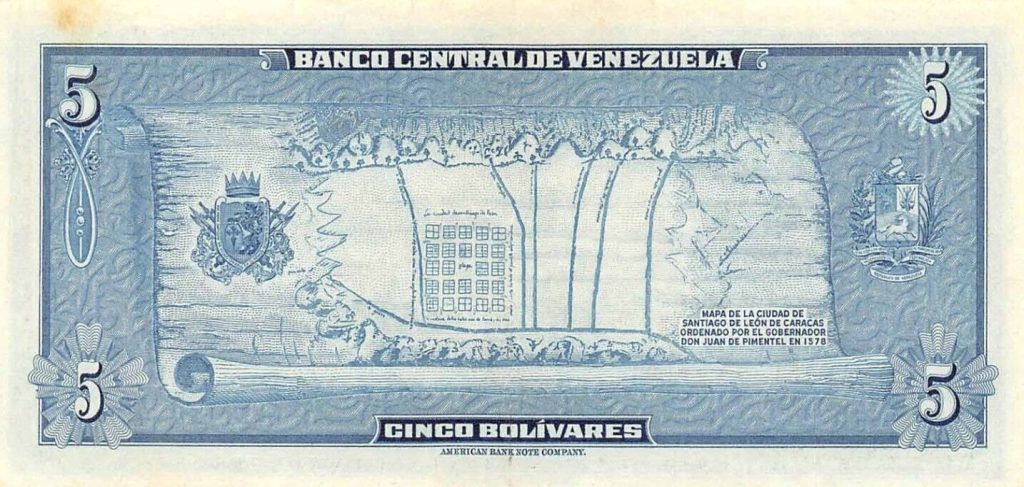

One of the most striking aspects of the commemorative 5 Bolívares banknote, issued in 1966, is the reverse side depiction of an early city plan of Caracas. This historical plan dates back to 1578, created under the orders of Governor Juan de Pimentel, who recognized the necessity of a more structured urban layout for the burgeoning settlement. While the drawing might appear rudimentary by modern standards, it was a groundbreaking vision for the period, representing an official acknowledgement of the city’s growth and significance.

In this plan, the careful linear arrangement of streets and blocks showcases the nascent stages of colonial urban planning—an approach heavily influenced by the Laws of the Indies. The central plaza, often accompanied by the cathedral and the main administrative offices, served as the nucleus from which the city’s life radiated outward. This representation reveals not only how foundational squares and thoroughfares were in the colonial imagination but also how meticulously the Spanish sought to replicate Old World cities in new territories.

Displaying this early map on the 5 Bolívares note was more than a tribute to the capital’s heritage. It served as a reminder that Caracas’s modernity rests on centuries of adaptation, experimentation, and the forging of new identities in a place born from the intersections of diverse cultures and histories. The banknote thus stands as both a reflection of Venezuela’s past and a testament to the enduring spirit of its people.

No figure looms larger in Venezuela’s quest for independence and national identity than Simón Bolívar, affectionately remembered as “El Libertador.” Born in Caracas in 1783, Bolívar was a child of privilege who received a cosmopolitan education in Europe. His exposure to Enlightenment ideals and witnessing the political shifts of his time ignited a passion for self-determination and liberation from colonial rule.

Upon returning to Venezuela, Bolívar found a society in the throes of discontent, with a growing number of creoles—people of European descent born in the Americas—tiring of Spanish overreach. Tapping into this spirit of rebellion, Bolívar assumed leadership roles in revolutionary campaigns, demonstrating both military acumen and diplomatic finesse. He believed not only in securing Venezuela’s freedom but also in forging a pan-continental unity among newly independent states, envisioning a grand republic that would bridge cultural and geographic divides.

Bolívar’s determination resulted in pivotal victories, such as the Battle of Carabobo in 1821, which effectively liberated Venezuela from Spain’s grip. Through strategic alliances and relentless military campaigns, he extended freedom to much of northern South America, establishing the foundations for nations like Colombia, Ecuador, and Bolivia—named in his honor. Yet his final years were shadowed by internal strife and the collapse of his dream for continental federation.

Still, Bolívar’s legacy endures beyond any single political outcome. He symbolizes the resilience, autonomy, and enduring courage of Venezuela and the broader region. His influence resonates in the designs of official emblems, currency, and public discourse, an ever-present reminder that the quest for self-determination and unity, though hard-won, remains at the heart of Venezuelan identity and aspiration.